When I started my literature research about New York, my hands first went to ‘Delirious New York’ by Rem Koolhaas, a very obvious choice.

When I started my literature research about New York, my hands first went to ‘Delirious New York’ by Rem Koolhaas, a very obvious choice.

‘Obvious’ doesn’t necessarily mean bad, not at all in this matter. Reading ‘Del NY’ helps you understand the Manhattanism better, extensively described by Rem Koolhaas.

MANHATTANISM = to exist in a world totally fabricated by man, i.e. to live ‘inside’ fantasy. Its program is so ambitious that to be realized, it could never be openly stated.

Some terms permanently linked to Manhattanism are THE GRID -its indifference to topography, to what exists, it claims the superiority of mental construction over reality-, THE BLOCK –everything has to be realized within it- and THE NEEDLE & THE GLOBE –those are representing two extremes, the history of Manhattanism is a dialectic between these two forms-.

After Koolhaas explains the important terms, he proceeds with a chapter only about Coney Island. Why Coney Island? Coney Island is the most southern part of Brooklyn. But most importantly it was a practice ground for the Manhattanism. The strategies and mechanisms that later shape Manhattan are tested in the laboratory of Coney Island.

After Koolhaas explains the important terms, he proceeds with a chapter only about Coney Island. Why Coney Island? Coney Island is the most southern part of Brooklyn. But most importantly it was a practice ground for the Manhattanism. The strategies and mechanisms that later shape Manhattan are tested in the laboratory of Coney Island.

It’s fascinating to learn how Coney Island transformed into the Coney Island we know today, because at that time there were three very different parts on one tiny island. Those three parts (the criminal area, the amusement parks and the resort part) may have coexisted but weren’t linked to each other.

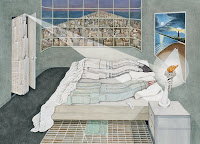

|

| Madelon Vriesendorp, Flagrant délit |

Koolhaas also clarifies the emergency of the Skyscraper –the double life of Utopia-, since 1900-1910. The Skyscraper represents the fortuitous meeting of three distinct urbanistic breakthroughs that, after relatively independent lives, converge to form a single mechanism: the reproduction of the world, the annexation of the tower and the block alone, the ‘the Automonoment’.He continues with some examples of transformations of city blocks and explains the showdowns between Modern Architecture and the architecture of Manhattanism.

From what I know about Brooklyn, the term Manhattanism doesn’t fit. Simply because Brooklyn isn’t Manhattan. At the moment, I could write down many other reasons. But I’ll come back to that later on, when I have done some more research about Brooklyn itself.

Source:Koolhaas, R. (1994). Delirious New York. A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. New York: The Monacelli Press

The ghetto, the inner city, the 'hood — these terms have been applied as monikers for black neighborhoods and conjure up images of places that are off-limits to outsiders, places to be avoided after sundown, and paragons of pathology. Portrayed as isolated pockets of deviance and despair, these neighborhoods have captured the imagination of journalists and social scientists who have chronicled the challenges and risks of living in such neighborhoods.

The ghetto, the inner city, the 'hood — these terms have been applied as monikers for black neighborhoods and conjure up images of places that are off-limits to outsiders, places to be avoided after sundown, and paragons of pathology. Portrayed as isolated pockets of deviance and despair, these neighborhoods have captured the imagination of journalists and social scientists who have chronicled the challenges and risks of living in such neighborhoods.