Running from the western waterfront of Brooklyn, at the Brooklyn Bridge Park, to the Van Wyck Expy in Queens, the Atlantic Avenue is a total of 16,5 kilometers long. Of these very divers 16,5 km, there is a notable different part of approximately three kilometers located in the neighborhood of Crown Heights, in between Bedford Avenue and Dewy Place. It varies from the other parts due to the elevation of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). That elevation creates a strengthening of the one-way, longitudinal direction of the Atlantic Avenue, mostly surounded by industrial/manufacturing buildings. The first element that created that longitudinal direction is the intense usage of the avenue by cars. Because of the high regularity of the columns of the above ground construction, there is also a wall created, which makes it more difficult to get a good look at the other side of the Atlantic Avenue. And again the longitudinal direction of the street is amplified by the monotonous use of the covered strip, under de LIRR. The only time when it's interrupted is when pedestrians cross the Atlantic Avenue, a use of a slower speed. They cross the street to get from their homes, in the residential area south of the Atlantic Avenue, to Fulton Street, a commercial axis with multiple subway stops. This link between these different important streets is fascinating because it is frequently used, but visual not distinct in the built environment.This connection is blocked by the closeness of the Atlantic Avenue and its facades. Those facades serve also as a soundbarrier against the LIRR, to the residential areas in Crown Heights south of the Atlantic Avenue and Bed-Stuy north of it. In between these two very strongly profiles axes is a residential zone, most of the time only half as wide as a normal building block and often mixed with other functions like public facilities.

By working on an urban scale I would want to propose to reveal this link between the Atlantic Avenue and Fulton Street. This by redefining the zone formed by those two, parallel streets and also the south side of the Atlantic Avenue. And why not make this other, transverse direction visible for the longitudinal-users like the train passengers or the motorists. Those connections wil not weaken the primary functions of the axes, but will connect them. Ending in a short design exercise of an intersection of the Atlantic Avenue and a perpendicular street.

Why not make these links litteral visible?

Why not make these links litteral visible?

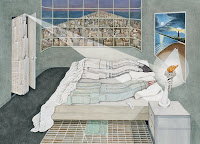

A view on both streets, Fulton Street and Atlantic Avenue.